I talked briefly about prediction markets in yesterday's Digital HR webinar, delivered with Knowledge Infusion (and I would have discussed crowdsourcing as well, if I'd had time!).

I talked briefly about prediction markets in yesterday's Digital HR webinar, delivered with Knowledge Infusion (and I would have discussed crowdsourcing as well, if I'd had time!).

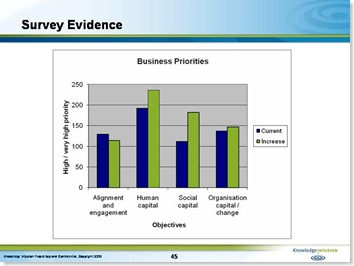

Like crowdsourcing, the basic idea here is to increase access and use of human capital, and in particular, for prediction markets, the perspectives of staff or others who are not normally involved in decision making.

A recent McKinsey article explains that:

"Initially a field of research, true prediction markets in essence are small-scale electronic markets, frequently open to any employee, that tie payoffs to measurable future events, such as sales data for a computer workstation, the number of bugs in an application, or a product’s usage patterns. Some companies, particularly in the high-tech sector, have adopted them in earnest, and a few major companies elsewhere are experimenting with them."

The markets work by aggregating the collective wisdom of the crowd and result in outputs which are at least as accurate as expert opinion:

"They work much like a futures market, in which the price of a contract reflects the collective day-to-day judgment either on a straight number—for instance, what level sales will reach over a certain period—or a probability—for example, the likelihood, measured as a percentage, that a product will hit a certain milestone by a certain date."

In a sense, therefore, this is a bit like nominal group technique (NGT), aided by technology, like an e-focus group, and then applied to specific, Y/N, or number based questions, and on a much larger scale.

The approach was developed at Best Buy, initially by just doing better forecasting with a simple survey. While not as sophisticated as a proper prediction market this approach still generated much better forecasts than the business had ever done before:

"Our first experiments at Best Buy were inspired by James [Surowiecki]’s book, and the results suggest that even a rudimentary survey strips away the filters that typically distort information as it moves higher in an organization.

At the time, I was managing the gift card business, which is a relatively small part of our portfolio, but I had a particular interest in it. We sent e-mails to hundreds of people throughout the company and asked them what they thought our gift card sales would be in February 2005. The only information we gave them as the context for their predictions was simple, readily available data. We got some 190 responses and ran a simple average. It turned out to be 99.5 percent accurate, whereas the people who got paid to forecast this were five percentage points off.

We ran a similar experiment later that year, when 350 random people predicted our holiday sales. Once again, the nonexperts, off by just one-tenth of 1 percent, were more accurate than the experts, who were off by 7 percent. The participants were surprised by the outcome when we shared it with them well after the actual results were in and reported. These early experiments encouraged us to get into prediction contracts, and we have to date seen over 2,000 traders make a total of 70,000 trades on 147 contracts."

And probably the leader in using prediction markets today is Google:

"We launched our prediction markets in April 2005, and since then we’ve asked about 275 different questions, and there’ve been some 80,000 trades. Around one-quarter of our markets have to do with demand forecasting—for instance, “How many people will use Gmail in the next three months?” Almost all Google products have had, or still have, a prediction market about their usage. Another 30 percent concern the company’s performance—for example, will project deadlines be met? A smaller category concerns things that could happen in our industry, such as mergers and acquisitions that might impact Google significantly."

Another perspective is provided by The New York Times:

"At Google, they are used, of course, for business. In the last two and a half years, 1,463 employees have made wagers with play money (Goobles, as in rubles) on questions like: will Google open a Russia office? will Apple release an Intel-based Mac? how many users will Gmail have at the end of the quarter? The lure, nominally, is accumulating those Goobles, which can be converted to modest prizes — $10,000 worth each quarter."

(You may also like to see an earlier post of mine on Google which covers its use of both crowdsourcing and prediction markets, and if you're really interested in this: a report, 'Using Prediction Markets to Track Information Flows: Evidence From Google').

A later New York Times article ('The Next Big Ideas: Placing Bets on the Wisdom of Employees - 20 April 2008 - sorry I can't find a link) discusses another interesting example of the use of prediction markets at InterContinental Hotels:

"Players were asked to submit ideas anonymously, with a description and the benefit for customers and company. The bettors were given virtual tokens, each receiving 10 green ones to be placed on the best ideas and three red for the bad ideas.

The five top ideas (most green tokens), five bottom ideas (most red) and the top five bettors (most accurate, according to market consensus) were listed regularly.

More than 200 people participated, submitting 85 ideas. Two projects have ben started as a result of the market."

So, same question I asked about crowdsourcing - what's this got to do with HR?

Well, firstly, this is just something HR practitioners need to be aware of, and where appropriate, introduce to their businesses as a tool to leverage their existing human capital. And I do think it should fall under HR's responsibility. Yes, the market itself is an IT tool, but the focus is on human capital, and that's HR's responsibility (a lot of HR departments already take responsibility for operating staff suggestion schemes - well this is simply an extension on that).

Also, prediction markets don't provide the same 'threat' to HR as crowdsourcing - we're talking about using the existing employee base rather than outsourcing it externally - but there's still an opportunity to think creatively about extending the range of human capital that's tapped through a predicted market, for example through the group of employee / partners who I discussed in my last post in order to increase the diversity of the market, achieving the 'law of large numbers'.

In the McKinsey article, James Surowiecki (The Wisdom of Crowds) comments that:

"For a crowd to be smart, it needs to satisfy certain criteria. It needs to be diverse, so that people are bringing different pieces of information to the table. It needs to be decentralized, so that no one at the top is dictating the crowd’s answer. It needs to summarize people’s opinions into one collective verdict. And the people in the crowd need to be independent, so that they pay attention mostly to their own information and don’t worry about what everyone around them thinks."

And Best Buy have noticed that forecasts about their main competitor have not been not very accurate which could also be down to lack of diversity amongst employees who are all involved in the same competitors. Involving employee / partners could be a good way to make prediction markets work more effectively.

But probably the biggest opportunity for HR is to use prediction markets as a tool to further raise understanding of the importance of human capital, and the increasing range of opportunities which exist to access and manage it.

James Surowiecki comments:

"The prediction markets trend is really part of a broader Web 2.0 bottom-up movement. There’s increasing recognition that large groups of people can solve problems together and come up with interesting answers, and that you don’t necessarily need formal hierarchies to accomplish this."

So, prediction markets (and other web 2.0 tools) provide useful support to help change an organisation's culture. But this is a chicken and the egg situation too. You need a reasonably well developed culture in order to get the best out of prediction markets / web 2.0 tools.

So, for example, in the McKinsey article, Jeff Severts from Best Buy notes:

"Corporations have a taboo against even considering the possibility that an important initiative may fail. To issue a contract that implies that this could happen is to betray the company in some way. So we found that support from very senior executives is essential if you want to issue contracts on anything that might be controversial. “Air cover” is a must or you’ll find yourself trading on what kind of casserole we’re having in the cafeteria on Thursday."

I'd like to say thank you to Veronique Briant for her New York Times article - sorry it's taken me so long to post!